Wrigley’s, Charles Green Shaw, 1935

As Franklin D. Roosevelt said, ‘Art is not a treasure in the past or an importation from another land, but part of the present life of all living and creating peoples.’ Such is the experience of the Royal Academy’s exhibition America After the Fall, which brings together 45 iconic paintings to tell the story of the 1930s depression. A time of great turmoil and transition, triggered by the Wall Street Crash of 1929, it was also one of creative flourish, as artists responded to a nation in flux – resulting in a vibrant, eclectic and very revealing display of art.

It begins with a packet of chewing gum. In Charles Green Shaw’s iconic painting, a Wrigley’s (1935) hovers in front of the Lower Manhattan skyline. Through the clean rectangular shapes, and the dreamy abstraction of the backdrop, the message appears to be clear: modern urban life is sexy. But it’s a vision that’s idealistic and, as suggested by the downward point of the logo, on the brink of drastic economic collapse. From this point on in the exhibition, the style of paintings becomes as various as the crises that rippled through the country.

Gas, Edward Hopper, 1940

In Edward Hopper’s paintings, for example, the city becomes a place of spiritual desolation. New York Movie (1939) carries a sense of disillusionment and nostalgia: the juxtaposition of the empty Hollywood fantasies in the shade, and the pensive usherette in the light, puts the so-called American Dream back in its place. The painting Gas (1940) also exemplifies Hopper’s clever use of light and shade to convey dramatic undertones. His lone figure at dusk on the edge of a country road carries a metaphysical charge: it’s an honest depiction of an American scene, but also probing and mysterious.

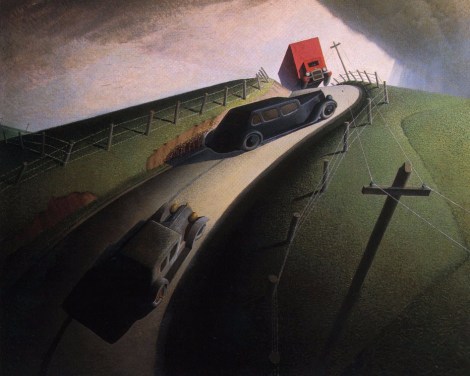

Country life became just as much a focus for artists, particularly those harking back to a rose-tinted view of America. Thomas Hart Benton’s paintings present images of rural harmony, where the countryside is a symbol of hope through turbulent times. Artists such as Grant Wood show a more ambiguous portrayal. His famous American Gothic (1930), for example, has been interpreted as both an image of the patriotic American spirit and also a satire of it. The quintessential is under scrutiny, something we see again in Death on the Ridge Road (1935), a painting which contrasts an idyllic green landscape with impending disaster.

Death on the Ridge Road, Grant Wood, 1935

The resemblance of the telephone pole to a cross in the Ridge Road painting is an interesting one. As the title of this exhibition addresses, there were strong biblical undertones to the ‘fall’ of American society; a kind of divine retribution on the economic and industrial greed that had corrupted American society. These ideas became starkly present in the work of Alexandre Hogue, notably in Mother Earth Laid Bare. An allusion to the ecological disasters of the Dust Bowl, the earth becomes a female figure, and the plow symbolises the rape of the land. His painting condemns the farming practices of humans and their disrespect of nature. In the fall of America, man is not to be sympathised with but to be blamed.

Nearing the end of the exhibition, the gloom enshrouding America becomes increasingly apparent. In Peter Blume’s Eternal City (1934-1937), Mussolini becomes a disturbing jack-in-the-box monster emerging from the Colosseum. The painting is heavily evocative of the fascist threat boiling away in Europe. There’s also Philip Guston’s disquieting cartoon realism in Bombardment, a grotesque entanglement of human and inhuman bodies during explosion. The painting was inspired by the newspaper reports of atrocities carried out during the Spanish a Civil War in 1936.

Mother Earth Laid Bare, Alexandre Hogue, 1938

The exhibition ends with some early examples of abstract expressionism, a movement that was to take hold of American art through the 40s and 50s. Alongside a work by Jackson Pollock, there’s also Swing Music by Arthur Dove, evocative of the dynamic jazz scene of the early century. Dove sought to draw a connection between painting and music, which he admired as being free of reference to the material world, a key component of the abstract expressionist style. We’re left feeling that this senselessness of form was borne from a desire to escape to troubling global realities of the 1930s.

Indeed, one of the merits of this exhibition is its timeliness in relation to two other Royal Academy shows. It’s an comprehensive precursor to Abstract Expressionism, and offers an intriguing historical parallel to Revolution: Russian Art. Considered alongside these, the body of work on display glows even more richly. But as an artistic illustration of the various political and social fears and ideas that shook 1930s America, it still offers a tight and intriguing narrative of its own.