Hatstand, Table, Chair (1969)

Few artists have exploded onto the scene with quite the scandalous gusto of Allen Jones. When he first unveiled the now-infamous Hatstand, Table and Chair in 1970, he sparked an immediate international sensation – for the sculptures depicted three life-size, bondage-clad female figures as items of furniture.

With second-wave feminism simultaneously on the rise, his work met with fierce accusations of misogyny: in 1978, protestors targeted a re-exhibition at the ICA with stink bombs; in 1986, a member of the public poured paint stripper over one of the offending pieces; and as affirmed by a 2014 retrospective at the RA, the cloud of controversy that has enshrouded Jones for the majority of his career has never quite cleared.

Admittedly, it’s not hard to see why. Particularly when considered against the liberal backdrop of the late 1960s, the figures conjure archaic stereotypes of women as domestic and sexual servants. One stands with hands upturned as hooks; one crouches on all fours with a glass surface resting on her back; the other lies with legs in the air as a back rest and her thighs as a seat cushion. They’re sadomasochistic, pornographic and grotesquely provocative.

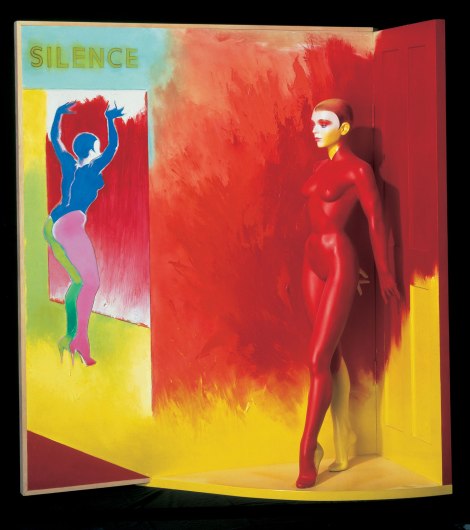

Stand In (1991/2)

Jones’ later works also perpetuate this festishistic aesthetic. Stand In (1991/2) infuses the female form with a kind of devilish power that becomes typical of his later works. His fibreglass sculpture Body Armour (2013), photographed being worn by Kate Moss, accentuates this figure with a fierce eroticism. Three-Part Invention (2002) show a scene of sexual indulgence with a liberated, brazen energy – with every work, the artist turns his audience into chance voyeurs.

Body Armour (2013)

To argue that Jones is a feminist might therefore seem a hopeless, if ludicrous assertion – and yet that is exactly what the artist declares himself to be. ‘I think of myself as a feminist’, he says, going so far as to profess allegiance with the very crowd he alienated: ‘I was reflecting on and commenting on exactly the same situation that was the source of the feminist movement’.

And indeed, for those prepared to see it, Jones’ artwork is heavily laden with ambiguous portrayals of gender. The interweaving of the sexes is a recurring theme: Man Woman (1963), for instance, shows the headless figures of a suited male and a flesh-baring female blurring indistinctly. First Step (1966) is even indicative of an inverted sexual dynamic: one leg stands elegant and robust, the other at once masculinised, restrained and fetishised by a tight sheet of grey.

First Step (1966)

His fixation with the female form also explores the mass-produced imagery of highly eroticised women of the 1960s, and how (or even whether) popular culture could become high art. He says that ‘the work came out of a preoccupation and a belief that it was possible to make a statement about the figure of the artistic avant garde of the 60s’, a concern that paralleled the world of fashion at the time.

There is something so deliberately bombastic about Jones’ figures that to renounce them as ‘degrading’ and ‘objectifying’ is a severely reductive way of looking at his oeuvre. There is no shying away from the sensationalist sexualisation of his female sculptures, for ultimately this is what they are: depictions of a sexist perception. But whether we view this as the artist’s attitude, rather than a deeper projection of society’s outlook, is highly debatable. In the same way that A. E. London’s harrowing paintings of endangered species does not make her opposed to animal rights, art can be used to address an issue without advocating it as well.

Jones is right to claim that his artworks have become the ‘perfect images for an argument about the objectification of women’. Some might say he has become scapegoated as part of the wider feminist agenda of his generation, stigmatised by the very attitudes he was critiquing. Whether he exposes how female stereotypes are performed or exploits these for creative novelty is ultimately up to the viewer to decide. But needless to say, this long-raging feminist debate has interfered with our full appreciation of Jones’ identity as an artist, one which deserves not to be pigeon-holed.